Guest blogpost by Adam Kullberg

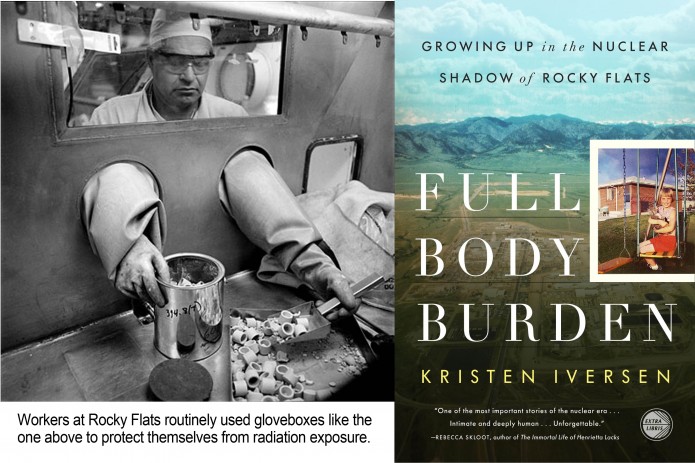

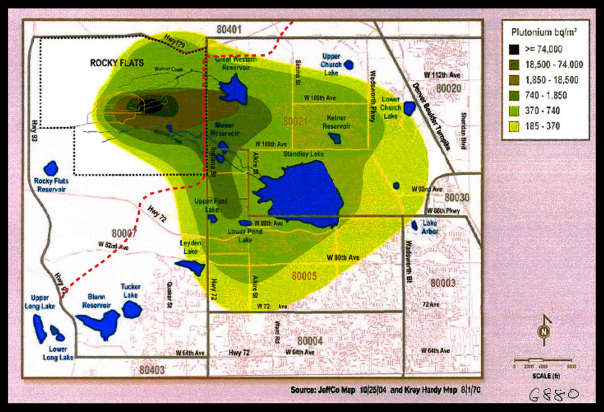

Kristen Iversen’s Full Body Burden: Growing Up in the Nuclear Shadow of Rocky Flats (Crown 2012) is a book about the power of secrets and of silence. In a masterful fusion of memoir and thought-provoking investigative journalism, Iversen braids together her less-than-ideal suburban childhood—peppered with an alcoholic father, a melancholic mother, and a neighborhood tinged with radioactive runoff—with the controversial Rocky Flats Plant near Denver, Colorado. Rocky Flats, open from 1952 to 1992, built plutonium triggers for the United States’ ever-growing nuclear stockpile during the Cold War. Employing a spectrum of artifacts, court records, press releases, and interviews, Iverson focuses her journalistic lens on the history, people, and repercussions of Rocky Flats. She reveals how the worlds we imagine we can isolate ourselves within, may so easily leach into and transform the worlds of others.

I resonate with Iversen’s story. Even before reading Full Body Burden, I thought myself a person who was familiar—even adept—with secrets. My grandfather and grandmother had worked at the Nevada Test Site (now the Nevada National Security Site) for over thirty years. Their jobs were something I knew about as a child, but only vaguely, and mostly thanks to the nights when my grandfather (usually after drinks) would nod his head toward the mountains to the North and hint cryptically that he had seen things “out there” that would make my jaw drop.

For a long time, I thought that these secrets made my grandfather and grandmother unique and somehow special. I didn’t begin to understand the consequences of the secrets until my grandmother died years ago from complications with her lungs. The sickness, my grandfather told me, was directly attributed to her work in underground bunkers at the Nevada Test Site (NTS) —a correlation that seems particularly true after I discovered that almost all her former NTS co–workers died in similar, if not identical, ways. Thankfully, my grandfather is still alive, but now he is battling two other incurable, lung-related illnesses.

My grandparents’ experience spurred my graduate school project this past summer. I set out to investigate the impact of nuclear technology and weaponry on the Southwest. Along the way, I also met families like mine—families who had lost one, two, three, or more members because of illnesses related to nuclear development and testing.

In Tularosa, New Mexico, I attended a candlelight vigil honoring local cancer victims and survivors in a small baseball field on the edge of town. (For newcomers to the blog, Olivia Fermi attended and spoke at similar ceremonies in 2010. Blogposts here and here.) I was beginning to see my grandparents’ story was not unique at all.

In August 2013, as part of my graduate school project, I toured the site of an old uranium mill near Moab, UT, that the EPA is cleaning up. On the same trip I visited the Grand Canyon and, in this photo, am standing on the south rim.” – Adam Kullberg

When I returned from my travels, I discovered Full Body Burden and Iversen’s account of yet another nuclear blunder: the controversial, sickening, and often outright villainous history of Rocky Flats. I now see a pattern: the Cold War mentality of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD) has, despite preventing nuclear havoc, left local communities torn apart and a whole new generation bearing the weight of our country’s collective radioactive legacy.

Iversen’s book is a tour de force. Through meticulous research, she’s able to give voice to differing perspectives about the plant’s impact on her community’s health, environment, and economy. She parallels Rocky Flats’ impact on the community with her family’s own steady decline, particularly through the characters of her increasingly distant, alcoholic father and her moody, melancholic mother. Just as Rocky Flats management created countless half-truths and foggy facts to cover up the plant’s true risks, we see Iversen’s family (and Iversen herself) desperately try to maintain a “rosy,” innocuous image for themselves and the outside world.

By examining these two histories in such close proximity, Iversen is able to highlight the discord between image and identity, truth, lies and secrets. Her father and mother seem a happy, confident couple in public. The neighborhood—chock-full of horses, wildlife, and surrounded by snow-capped mountain ranges—seems to be a safe place to grow up; and Rocky Flats seems (as many employees claim throughout the book) to be one of the “safest places” to work in the United States. Yet, in her life, and in this book, the realities and toxicities bubbling up from under the surface become increasingly stark and all too tragic.

As the narrative unfolds, Iversen’s father’s mental and physical health continues to decline, and eventually he simply drifts out of range of the family. Her classmates and neighborhood friends suffer and some die from a variety of radiation-related ailments. She reveals Rocky Flats to be a production-focused place in which managers overlook plutonium leaks, dangerous chemicals are scattered throughout the grounds in leaky containers and employees poke holes in safety vents to meet quotas. Iversen openly shares the stress of her own mysteriously swollen lymph node, and the worries about the safety of her children, as she pieces together her intimate relationship to Rocky Flats. Powerfully, we as readers begin to see how we, too, are tied into the history of Rocky Flats—through our bodies, our minds, and our unknown futures. We can see how the secrets and tragedies of one place change both public and private concerns, radiating through the landscape, through families, and across generations.

At the end of Full Body Burden, Iversen underscores the theme of secrecy by pointing out, even today, almost two decades after Rocky Flats has been closed to the public, and despite its transformation into a National Wildlife Refuge almost 15 years ago, there are still arguments about what is fact, what is fiction, and what still needs to be kept hidden under the veil of secrecy. “We don’t talk about plutonium,” she explains, “It reminds us of what we don’t want to acknowledge about ourselves. We built nuclear bombs, and we poisoned ourselves in the process. Where does the fault lie?”

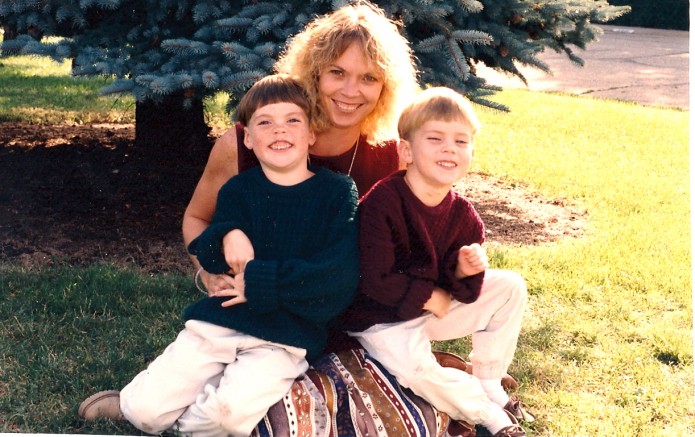

Kristen Iversen with her sons Sean & Nathan. Photo taken during the time Iversen herself worked at Rocky Flats.

I applaud Iversen for taking out her shovel and revealing all she found in Full Body Burden. In so doing, she encourages us to do the same. “To speak out or to remain silent is the first and most crucial decision we can make,” she says in the final line. Perhaps, once we understand that we are responsible not only for what we say, but what we do not say, we will be able to change the worlds around, between, and within us for the better.

Adam Kullberg is an MFA candidate in nonfiction at the University of Arizona, graduating in December 2013. He is currently working on a collection of essays that deal with the legacy of nuclear weapons and technology, focusing particularly on their impact upon his own family and throughout the Southwest.

Twitter

Twitter